Before I release this series of articles, I just want to say that I am unbelievably bullish on the world and think that we are generally taking steps in the right direction to a more sustainable future. That said, I have some thoughts, observations, and ideas that I am excited to share about the risk we are in related to unprecedented global debt. I have no idea what the timing of any of this will be- or if it will ever happen- but at this rate, it’s hard to imagine something not giving. I am more excited about this three part piece of literature that I've put together as my senior capstone Wharton graduation project than anything else I've ever released.

The Greater Recession, by Elijah Levine

It’s greater this time because it’s commercial real estate, not residential, which will have resounding impacts even at the consumer level throughout the entire global economy.

Just like leading up to the 2008 Great Financial Crisis when residential real estate was being massively over-levered, there has been a massive over-leveraging in the commercial real estate space. Not in just office, but multifamily, industrial, retail, hospitality, single family, and honestly many more industries beyond real estate- it's just that real estate notoriously has more debt than almost pretty much any other industry.

It’s easy math, if a business is yielding 8% pre-debt, which is somewhat standard for most stabilized real estate projects (oftentimes even lower), and that business has 3% floating rate debt, they are yielding 5% post-debt payments, not too bad.

However, now that interest rates have risen ~4%, all businesses with floating rate debt are now subject to much higher debt payments and therefore lower post-debt yields. Based on my experience talking with numerous industry leaders and underwriting hundreds of billions of dollars of assets, I know for a fact that many businesses were operating on floating rate debt under the assumption that rates would not rise to the level they are now at.

This means that many businesses are going to be unable to service their debt and therefore either go bankrupt or be forced to refinance in a very serious way. This goes for not only real estate businesses, but banks and the US government.

In the above example, that 5% post-debt yielding business would now only be yielding 1%. The question then becomes, but what impact does this have on value?

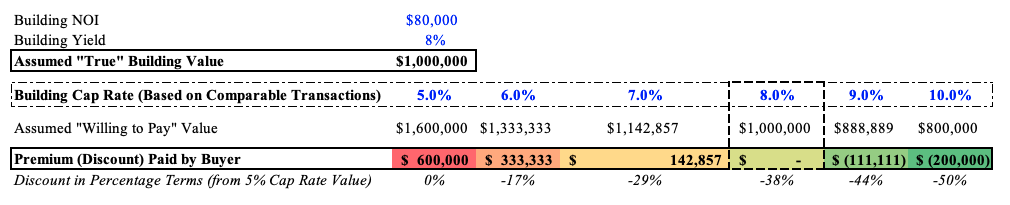

To build on this example, let’s say the building is yielding, pre-debt, $80k/year of “net operating income.” Now here’s where it gets interesting when it comes to the impact on value and up for debate, or negotiation, usually using recent comparable transactions as a starting point for those discussions. The problem is that there is currently a very limited number of comparable transactions for reasons I wrote about in a lot more detail in an article called “The Macroeconomic Tug of War of Today” late last year.

If somebody was willing to pay a 5% cap rate (a real estate valuation tool similar to a PE ratio in public markets, calculated using the formula CAP RATE = NOI / PURCHASE PRICE) for that business yielding $80k/year of NOI, that person would be buying that business for $1.6m, a 60% premium for just a 3% difference in pre-debt yield versus willingness to pay in terms of the cap rate valuation. This is a fascinating phenomenon and why cap rates usually stay in certain bounds over time- because they have a gigantic impact on value.

But where do cap rates come from? Comparable transactions. These transactions are usually very opaque in the world of commercial real estate anyway, but because of this massive tug of war happening across all markets, especially the already illiquid commercial real estate markets, even less transitions are happening- and those that are transacting are often being kept under wraps.

In the above example, if the cap rate of that building increased 3%, which would be a very dramatic occurrence, the building’s value (according to the above formula) would be reduced to ~1m, a 38% reduction in value from the 5% cap rate value.

A more realistic example would be the cap rate rising to 6.5%, resulting in a ~$1.23m value and ~23% reduction from the 5% cap rate value. I think we are going to start to see more of these sort of price reductions happen once sellers start to wake up to the reality of “higher for longer.”

Although cap rates do not necessarily have to do with debt in terms of the formula, they tend to move in tandem as both valuation and debt payments are a matter of liquidity- or how much money is available to transact in any given marketplace. For the most part, buyers have more leverage or buying power than sellers in most markets since a lot of the bubble that was created had to do with owners (current sellers) putting insane amounts of debt onto their buildings without considering scenarios of interest rate increases...

I think people are slowly but surely waking up to this but that most people are genuinely terrified to admit just how big of a problem it is. Things have not been transacting for a reason, and it’s because not only are buyers and sellers in trouble, but banks too. Banks don’t necessarily want to repossess assets with bad debt, and refinancing at lower valuations isn’t good for anybody.

A very dramatic recent example of this is an office building in St. Louis that was transacted for $205M in 2006 just this month being sold for $3.6M. Once again, we are in an unprecedented time of price discovery and it’s essentially a massive game of poker. I couldn’t be more excited about it but I also understand how potentially dangerous it is on a global scale. Global conflicts are also destroying value- dollars, to be exact, which means that the dollar price of what value truly is needs to be discovered at some point. The big question is, what will that be?

Of course, it will depend on the market and the liquidity found within each of those markets. For example, Dubai has 10-20x the buildings of Baltimore but only ~5.8x the population. Is there over building? Could Dubai be heading to a situation like the ghost cities seen in tertiary markets in China? I personally don’t think so, but it’s certainly not impossible.

In the last year and a half, I’ve visited Singapore, LA, Salt Lake City, San Fransisco, Baltimore, New York, Washington DC, Philadelphia, Park City, Sun Valley, Miami, and probably a few other cities. In almost all of them, there has been under-building. This has led prices to be pushed up because there is less supply than there is demand for renting and owning living spaces.

There are some exceptions to this, however, such as Baltimore and San Francisco, and to a much smaller degree, Philadelphia- where I have been living on and off for the last ~6 years. The interesting thing is though, even though they are in the same country (on opposite ends, fairly), SF and Baltimore have an unbelievable price disparity.

For example, a two bedroom townhome in Baltimore is going for $200-300k, even if not in the worst of areas. In San Francisco, most two bedrooms are well over $1.2m despite both cities being perceived as very dangerous and for the most part, empty. There is clearly a big difference in what people are willing to pay for. Is this location, is this quality of asset- and if neither of these things, what is it? I think it’s landmass, liquidity, quality of life, talent and opportunity, similar-minded people, and more- among other things.

Something big is happening in terms of global liquidity, what that means for prices, I don’t think anybody really has any idea- other than maybe the largest companies with the best and most sophisticated economic analysis models, but even those guys really don’t know. That means what every deal will come down to is how much the other side is willing to settle on.

This will be inconsistent across asset class, across geographies, and across time. But one thing is for certain, higher interests are going to cause prices to come down across the board, and we are just now starting to see this happen. Who will be the winners? Read the next article in this series to see how “REITs” might be the industries’ saving grace in these wildly exciting times.